Celtic father-names: Donaldson, McDonald, O’Donnell

- Stefan Israel

- Mar 17, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 6, 2023

We talked about patronymics (the father’s name) in Germanic languages earlier, how about in Celtic languages?

“Donald” is a Celtic name of long standing, and if you want to state that someone is the son of a Donald, you can call them Donaldson- in the English tradition. But since it’s a Celtic name, you usually see it as McDonald in the Scottish tradition, or O’Donnell in the Irish tradition.

The main Celtic traditions for genealogy are the Irish, the Scottish and the Welsh.

Complicating matters, Irish settlers brought Gaelic from Ireland to Scotland in the early Middle Ages, so Irish Gaelic and Scots Gaelic are closely related; Welsh leads a different branch of the Celtic languages. To complicate things more, many Scots moved to Ireland, bringing their Scots names, while the Lowlands of Scotland adopted their variety of English called Scots Leid, in the Dark and Middle Ages. Scots Leid is not a Celtic language, but Celtic influences permeated into the Lowlands as well. All the languages of the British Isles intermingle one way or another.

Gaelic

Irish Gaelic (sounds like “gay-lik”) and Scots Gaelic (sounds like “gal-lik”) are closely related, and once the names have been anglicized, it can be hard to tell which language the name came from. The easiest way is to see which is which is when they form a patronymic, usually Mac- or O’-.

Mac was the word for ‘son (of)’, and O’ (or more Irishly, Ua) was the word for ‘descendent (of)’. The Scots use Mac- and the Irish use O’... but it’s only a short hop across the Irish Sea, don’t be surprised if names make that hop, especially the Scotch-Irish, who moved from Scotland to Ireland to America.

Mac/Mc = ‘son of’ O’ (Ua) = ‘descendent of’

In the Gaelic language itself (itsselves, there’s Irish Gaelic and Scots Gaelic), it’s more complicated: instead of saying ‘of’, the name itself morphs in ways too complicated for this short blog. And since documentation has generally been in English and Latin, you won’t often see the full Celtic complexity.

Just as an example, the Irish Gaelic form of Donald is Dónall or Domhnall, “Ruler of the World”- but if you want to say “of Donald”, the form shifts to Dhönaill. Thus MacDonald in Scots Gaelic is Mac Dhòmhnaill, and yes, the change in spelling reflects changes in pronunciation, in ways English does not do.

The Irish turn Dónall into Ó Dónaill, which we know as O’Donnell.

In Gaelic, since mac means ‘son of’, naturally you need a way to say ‘daughter of’, even if the English tradition did not pick up on it.

Mac/Mc = ‘son of’

Ní = ‘daughter of’

(Bean) Mhic ‘wife of the son of’

O’ (actually Ua) = ‘descendent of’

Nic = ‘female descendent of’

(Bean) Ui ‘wife of the descendent of’

Thus Nic Dhónaill and Bean Uí Dhónaill are the feminine equivalent of O’Donnell.

The name of the Irish singer Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh would translate as Mary daughter of Mooney- the English pronunciation of her name is “Mary nee Weenee”, and the actual Irish pronunciation is much more complicated. That gives you a little sense of how much Gaelic words change in the course of a phrase.

Mairead talking and singing in Irish Gaelic

Governments, which have been English-speaking in Celtic lands for centuries, have wanted unchanging family names to track real estate and the like, but the local community often wanted to know who’s related how, so they might refer to Sean, Pol’s son and Shamus’s grandson as Seán Phóil Shéamuis as well as Seán Ó Cathasaigh- if you follow Irish literature, you’ll know him in English as Seán O'Casey.

And if you want to identify someone by their mother or grandmother, you could rattle off their genealogy that way just as easy.

Welsh

We must not forget the Welsh, the third of the major Celtic nations! They do not loudly celebrate their traditions to the world the way the Irish and the Scottish communities do, and yet, for all the centuries living cheek by jowl with the English, Yma O Hyd, Welsh for ‘We’re Still Here’

Welsh band Ar Log singing Yma O Hyd: We're Still Here

Welsh words (or Brittonic, which includes some related sister languages) change just as remarkably as the Gaelic ones do, and what turned into mac- in Gaelic (from an earlier makw-) lost the m and systematically change the kw into p, so Welsh for ‘son of’ is ap (or ab in some instances), and ‘daughter’ is ferch (“vairkh”). The Gaelic patronymics tended to become family names, while the Welsh kept up true patronyms much longer, that is, changing every generation, since it states your father’s name. And again, they might cite a chain of ancestors:

Llewelyn ap Dafydd ab Ieuan ap Gruffudd ap Meredydd

‘Llewelyn son of David son of Evan son of Griffith son of Meredith’

Unchanging family names did win out by the early 1800’s, but if you trace Welsh roots further back, be prepared for family names to peter out.

And caution here as well! With so many ‘last names’ based on the current father’s first name, many small communities would have many ‘son-of-John’s etc. who are not related; Jones, Williams, Evans, Davies and Thomas are the most common of such names, and neighbors of the same name might have no family connection at all, only an ancestor with the same first name.

The ‘son of’ word ap would also be reduced to a P- that fused into the name, giving us these familiar ‘English’ names:

ap John > Upjohn or Jones

ap Hywel > Howell or Powell

ap Rhys > Price

ap Richard > Prichard

ab Owen > Bowen

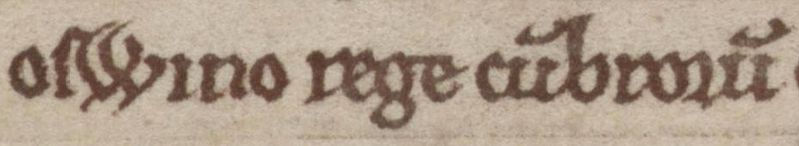

And let’s close with Owen ap Dyfnwal, a Brittonic king of the 900’s, “Owen son of Donald.” Mac- or ap or O’, it’s all Celtic.

Commentaires